Neuroscientists from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore), University of Pennsylvania, and California State University, have established the existence of a biological difference between psychopathic individuals and non-psychopaths.

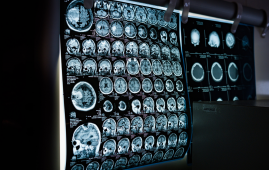

Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, they found that a region of the forebrain known as the striatum, was on average 10% larger in psychopathic individuals compared to a control group of individuals that had low or no psychopathic traits.

Psychopaths, or those with psychopathic traits, are generally defined as individuals that have an egocentric and antisocial personality. This is normally marked by a lack of remorse for their actions, a lack of empathy for others, and often criminal tendencies.

The striatum, which is a part of the forebrain, the subcortical region of the brain that contains the entire cerebrum, coordinates multiple aspects of cognition, including both motor and action planning, decision-making, motivation, reinforcement, and reward perception.

Previous studies have pointed to an overly active striatum in psychopaths but have not conclusively determined the impact of its size on behaviors. The new study reveals a significant biological difference between people who have psychopathic traits and those who do not.

While not all individuals with psychopathic traits end up breaking the law, and not all criminals meet the criteria for psychopathy, there is a marked correlation. There is clear evidence that psychopathy is linked to more violent behavior.

The understanding of the role of biology in antisocial and criminal behavior may help improve existing theories of behavior, as well as inform policy and treatment options.

To conduct their study, the neuroscientists scanned the brains of 120 participants in the United States and interviewed them using the Psychopathy Checklist—Revised, a psychological assessment tool to determine the presence of psychopathic traits in individuals.

Assistant Professor Olivia Choy, from NTU’s School of Social Sciences, a neurocriminologist who co-authored the study, said: “Our study’s results help advance our knowledge about what underlies antisocial behavior such as psychopathy. We find that in addition to social environmental influences, it is important to consider that there can be differences in biology, in this case, the size of brain structures, between antisocial and non-antisocial individuals.”

Professor Adrian Raine from the Departments of Criminology, Psychiatry, and Psychology at University of Pennsylvania, who co-authored the study, said: “Because biological traits, such as the size of one’s striatum, can be inherited to child from parent, these findings give added support to neurodevelopmental perspectives of psychopathy—that the brains of these offenders do not develop normally throughout childhood and adolescence.”

Professor Robert Schug from the School of Criminology, Criminal Justice, and Emergency Management at California State University, Long Beach, who co-authored the study, said: “The use of the Psychopathy Checklist—Revised in a community sample remains a novel scientific approach: Helping us understand psychopathic traits in individuals who are not in jails and prisons, but rather in those who walk among us each day.”

Highlighting the significance of the work done by the joint research team, Associate Professor Andrea Glenn from the Department of Psychology of The University of Alabama, who is not involved in the research, said: “By replicating and extending prior work, this study increases our confidence that psychopathy is associated with structural differences in the striatum, a brain region that is important in a variety of processes important for cognitive and social functioning. Future studies will be needed to understand the factors that may contribute to these structural differences.”

The results of the study were published recently in the peer-reviewed academic publication Journal of Psychiatric Research.

Bigger striatum, larger appetite for stimulation

Through analyses of the MRI scans and results from the interviews to screen for psychopathy, the researchers linked having a larger striatum to an increased need for stimulation, through thrills and excitement, and a higher likelihood of impulsive behaviors.

The striatum is part of the basal ganglia, which is made up of clusters of neurons deep in the center of the brain. The basal ganglia receive signals from the cerebral cortex, which controls cognition, social behavior, and discerning which sensory information warrants attention.

In the past two decades, however, the understanding of the striatum has expanded, yielding hints that the region is linked to difficulties in social behavior.

Previous studies have not addressed whether striatal enlargement is observed in adult females with psychopathic traits.

The neuroscientists say that within their study of 120 individuals, they examined 12 females and observed, for the first time, that psychopathy was linked to an enlarged striatum in females, just as in males. In human development, the striatum typically becomes smaller as a child matures, suggesting that psychopathy could be related to differences in how the brain develops.

Asst Prof Choy added: “A better understanding of the striatum’s development is still needed. Many factors are likely involved in why one individual is more likely to have psychopathic traits than another individual. Psychopathy can be linked to a structural abnormality in the brain that may be developmental in nature. At the same time, it is important to acknowledge that the environment can also have effects on the structure of the striatum.”

Prof Raine added: “We have always known that psychopaths go to extreme lengths to seek out rewards, including criminal activities that involve property, sex, and drugs. We are now finding out a neurobiological underpinning of this impulsive and stimulating behavior in the form of enlargement to the striatum, a key brain area involved in rewards.”

Leave a Comment