Just like cars, houses, or neighborhoods differ in how they age, different parts of our bodies also age at different speeds. A recent study conducted by researchers from Stanford Medicine, involving 5,678 participants, revealed that our organs do not age uniformly. If a specific organ aging is faster compared to the same organ in others of the same age group, the person with the faster-aging organ is more vulnerable to diseases related to that organ, causing organ failure, and has a higher risk of mortality.

The research suggests that approximately 20% of generally healthy adults aged 50 and above have at least one organ aging faster than usual.

The positive aspect is that a basic blood test might be able to identify which organs are aging quickly in a person’s body. This could help in starting treatments early, even before any noticeable symptoms appear.

“We can estimate the biological age of an organ in an apparently healthy person,” said the study’s senior author, Tony Wyss-Coray, Ph.D., a professor of neurology and the D. H. Chen Professor II. “That, in turn, predicts a person’s risk for disease related to that organ.”

Hamilton Oh and Jarod Rutledge, students in Wyss-Coray’s lab, are the main writers of the study, released online on Dec. 6 in Nature.

Biological versus chronological age

“Numerous studies have come up with single numbers representing individuals’ biological age—the age implied by a sophisticated array of biomarkers—as opposed to their chronical age, the actual numbers of years that have passed since their birth,” said Wyss-Coray, who is also the director of the Phil and Penny Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience.

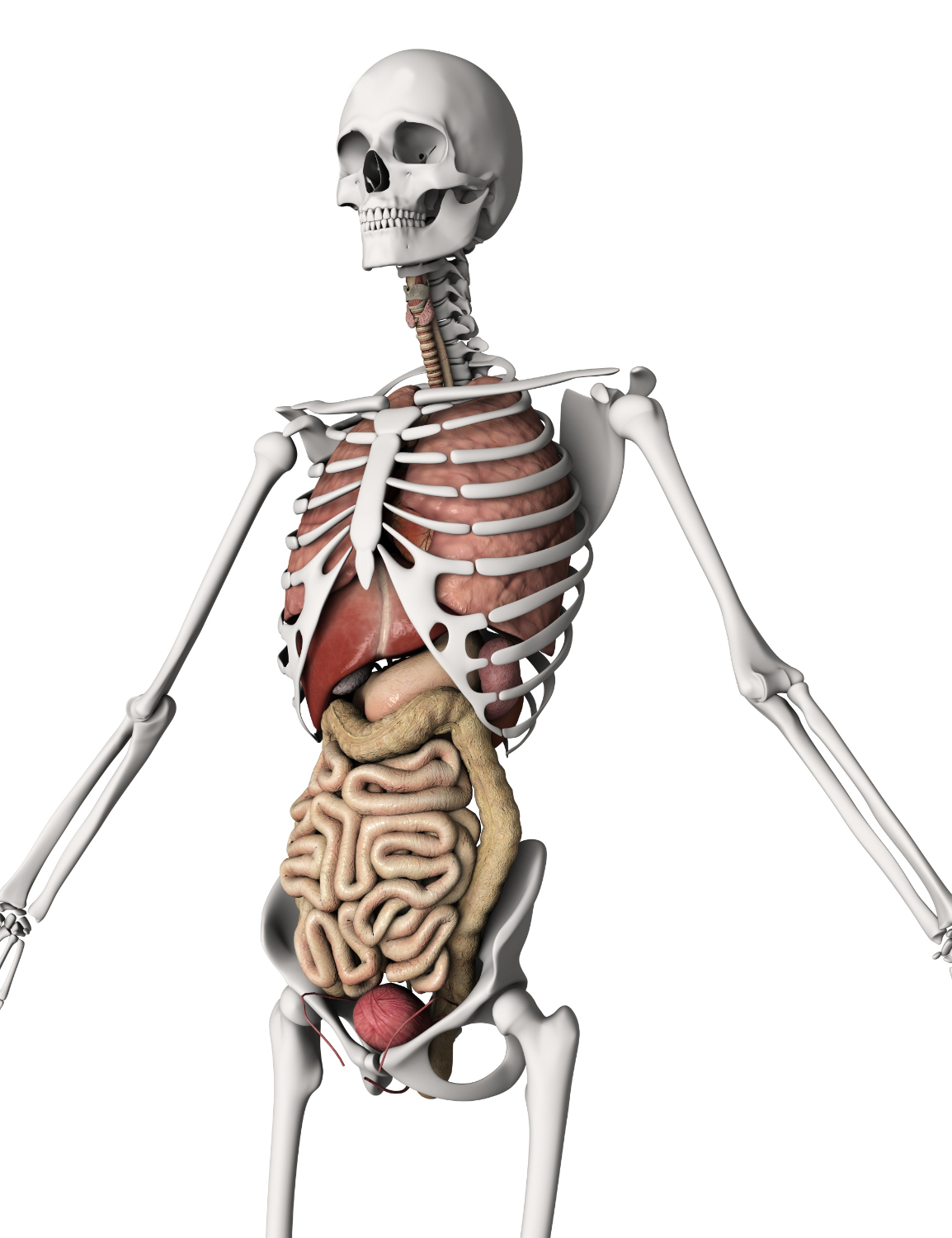

It provided specific numbers for 11 important parts of the body, including the heart, fat, lungs, immune system, kidneys, liver, muscles, pancreas, brain, blood vessels, and intestines.

“When we compared each of these organs’ biological age for each individual with its counterparts among a large group of people without obvious severe diseases, we found that 18.4% of those age 50 or older had at least one organ aging significantly more rapidly than the average,” Wyss-Coray said. “And we found that these individuals are at heightened risk for disease in that particular organ in the next 15 years.”

In the research, only approximately one in every 60 individuals experienced rapid aging in two of their organs. However, Wyss-Coray said, “They had 6.5 times the mortality risk of somebody without any pronouncedly-aged organ.”

The researchers used commercial technologies and their own algorithm to analyze thousands of proteins in people’s blood. They discovered that almost 1,000 of these proteins came specifically from individual organs. Abnormal levels of these proteins were linked to faster aging and increased vulnerability to diseases and death in those corresponding organs.

They began by examining the protein levels in the blood of almost 5,000 individuals, aged 20 to 90, who were generally healthy but mostly in the later stages of life. They identified proteins whose genes were four times more active in one organ than in any other. Initially, they found around 900 proteins specific to certain organs, but for reliability, they narrowed it down to 858.

To achieve this, they taught a machine-learning algorithm to estimate people’s ages by considering the levels of those 5,000 proteins. The algorithm selects proteins that most closely align with a specific characteristic (in this instance, accelerated biological aging in an individual or a specific organ) by asking, one after another, “Does this protein improve the correlation?”

The researchers confirmed the algorithm’s precision by evaluating the ages of around 4,000 individuals, who were reasonably reflective of the U.S. population.

Following this, they employed the proteins they had identified to focus on each of the 11 organs chosen for examination. They measured the levels of organ-specific proteins in each person’s blood.

Despite some minimal aging alignment among distinct organs within an individual’s body, the aging trajectory of each person’s specific organs generally followed independent paths.

Organ aging gap

For each of the 11 organs, Wyss-Coray’s team determined an “age gap”: the variance between an organ’s real age and its estimated age derived from the algorithm’s organ-specific protein-driven computations. The scientists observed that the identified age gaps for 10 out of the 11 studied organs (except the intestine) were markedly linked to the future risk of death from all causes over a 15-year follow-up period.

Possessing an organ with accelerated aging (characterized by a 1-standard deviation higher algorithm-scored biological age compared to the group average for that organ in individuals of the same chronological age) was linked to a 15% to 50% increased risk of mortality over the subsequent 15 years, depending on the affected organ.

Individuals experiencing accelerated aging in the heart, yet showing no signs of active disease or clinically abnormal biomarkers initially, faced a 2.5 times greater risk of heart failure compared to those with hearts aging at a normal rate, according to the study.

Individuals with “older” brains were 1.8 times more likely to experience cognitive decline over five years compared to those with “young” brains. Accelerated aging in either the brain or vasculature predicted the risk of Alzheimer’s disease progression as effectively as the currently best-used clinical biomarkers.

Similarly, there were significant connections between an extreme-aging kidney score (more than 2 standard deviations above the norm) and both hypertension and diabetes, as well as between an extreme-aging heart score and both atrial fibrillation and heart attack.

“If we can reproduce this finding in 50,000 or 100,000 individuals,” Wyss-Coray said, “it will mean that by monitoring the health of individual organs in apparently healthy people, we might be able to find organs that are undergoing accelerated aging in people’s bodies, and we might be able to treat people before they get sick.”

According to the researcher, finding the proteins specific to each organ that most accurately signal advanced organ aging and, consequently, increased risk of disease could also open up possibilities for discovering new drug targets.

More information: Tony Wyss-Coray, Organ aging signatures in the plasma proteome track health and disease, Nature (2023).

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06802-1. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06802-1

Provided by Stanford University Medical Center

more recommended stories

T-bet and the Genetic Control of Memory B Cell Differentiation

T-bet and the Genetic Control of Memory B Cell DifferentiationIn a major advancement in immunology,.

Ultra-Processed Foods May Harm Brain Health in Children

Ultra-Processed Foods May Harm Brain Health in ChildrenUltra-Processed Foods Linked to Cognitive and.

Parkinson’s Disease Care Advances with Weekly Injectable

Parkinson’s Disease Care Advances with Weekly InjectableA new weekly injectable formulation of.

Brain’s Biological Age Emerges as Key Health Risk Indicator

Brain’s Biological Age Emerges as Key Health Risk IndicatorClinical Significance of Brain Age in.

Children’s Health in the United States is Declining!

Children’s Health in the United States is Declining!Summary: A comprehensive analysis of U.S..

Autoimmune Disorders: ADA2 as a Therapeutic Target

Autoimmune Disorders: ADA2 as a Therapeutic TargetAdenosine deaminase 2 (ADA2) has emerged.

Is Prediabetes Reversible through Exercise?

Is Prediabetes Reversible through Exercise?150 Minutes of Weekly Exercise May.

New Blood Cancer Model Unveils Drug Resistance

New Blood Cancer Model Unveils Drug ResistanceNew Lab Model Reveals Gene Mutation.

Healthy Habits Slash Diverticulitis Risk in Half: Clinical Insights

Healthy Habits Slash Diverticulitis Risk in Half: Clinical InsightsHealthy Habits Slash Diverticulitis Risk in.

Caffeine and SIDS: A New Prevention Theory

Caffeine and SIDS: A New Prevention TheoryFor the first time in decades,.

Leave a Comment