A preclinical study conducted by Weill Cornell Medicine researchers reveals that a certain human genetic variant of an insulin-stimulating receptor may help individuals be more resistant to obesity. This version functions differently in the cell, which may lead to more effective metabolism, according to the researchers.

The researchers created mice with a human genetic variation in the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor, which has been linked to a lower BMI. The mice were shown to be better at sugar processing and keeping slimmer than mice with a different, more common form of the receptor. The discovery could lead to new treatment options for obesity, which affects more than a hundred million adults in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Our work demonstrates how basic science research can yield important insights into complex biology,” said senior author Dr. Timothy McGraw, a cardiothoracic surgery and biochemistry professor at Weill Cornell Medicine. “These GIP receptors and their behavior at the cellular level profoundly impact metabolism and weight regulation.”

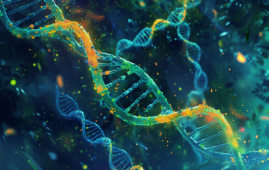

GIP Receptor Genetic Variants

Differences in DNA sequence that occur spontaneously between people in a particular group are referred to as genetic variations. According to genome-wide association studies, which use statistics to meticulously link genetic variants to specific traits, approximately 20% of persons of European origin have one copy of the GIP receptor with the Q354 gene mutation, while approximately 5% have two copies. The GIP receptor interacts with a hormone secreted in response to post-meal glucose levels. “Studies suggest that people with at least one copy of this GIP receptor variant have altered metabolism, which reduces their risk of developing obesity,” said Dr. Lucie Yammine, a post-doctoral associate in biochemistry at Weill Cornell Medicine.

To learn more about how this gene variant may reduce the risk of obesity, the researchers employed CRISPR-Cas9 technology to genetically modify mice with the variant in the gene encoding the GIP receptor that is similar to the human version. Female mice with the variation were found to be slimmer on a standard mouse diet than female littermates without it. Male mice with the gene mutation weighed about the same as litter mates without it on a regular diet, but it protected them from weight gain when fed a high-fat diet, which caused obesity in litter mates.

“We found that a change in one amino acid in the GIP receptor gene affected the whole body in terms of weight,” said Dr. Yammine. Mice with the variation were more sensitive to the GIP hormone, which stimulates the production of insulin, which regulates blood sugar levels and aids the body in the conversion of food into energy.

How the Variant May Be Beneficial Against Obesity

When exposed to glucose or the GIP hormone, the researchers evaluated what happened to mouse cells with and without the variation. Pancreatic cells from mice with the genetic mutation released more insulin in response to both glucose and the GIP hormone, which could explain why they handle glucose better.

What’s interesting about these receptors is their location in the cell has a big impact on how they signal and their activity,” said Dr. McGraw. When the GIP hormone binds to the receptor, the receptor travels from the cell surface to the inside. The receptor returns to the cell surface when the GIP hormone breaks off the receptor.

The researchers discovered that the GIP receptor variation remains inside the cell compartment four times longer than the standard receptor. According to Dr. McGraw, this may allow the receptor to deliver more information to the machinery inside cells, allowing for more efficient sugar metabolism.

More research is needed to confirm the implications of this variation on the functioning of the receptor. The researchers also want to know if there are changes in the behavior of the receptor in other cell types, such as brain cells, which play an important role in regulating appetite.

The Food and Drug Administration recently approved several weight reduction medicines, including semaglutide (Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Zepbound), that imitate natural hormones in the body and interact with receptors like GIP. This has heightened interest in researching new strategies to target the GIP receptor for obesity treatment.

“Our findings suggest that receptor movement from the cell surface to the interior is an important factor in metabolism control.” “As a result, drugs that can regulate GIP receptor behavior and location could provide an important new avenue for combating obesity,” Dr. Yammine added.

Meanwhile, Dr. McGraw emphasized the importance of understanding how patients with different genetic variations in the GIP receptor respond to currently available weight loss medicines. “A better appreciation of how different variants of receptors impact metabolism might allow for a precision medicine approach — matching a specific drug to a genetic variant — for weight loss,” he added.

For more information: Spatiotemporal regulation of GIPR signaling impacts glucose homeostasis as revealed in studies of a common GIPR variant. Molecular Metabolism, 2023; 78: 101831 DOI: 10.1016/j.molmet.2023.101831

more recommended stories

Can Ketogenic Diets Help PCOS? Meta-Analysis Insights

Can Ketogenic Diets Help PCOS? Meta-Analysis InsightsKey Takeaways (Quick Summary) A Clinical.

Silica Nanomatrix Boosts Dendritic Cell Cancer Therapy

Silica Nanomatrix Boosts Dendritic Cell Cancer TherapyKey Points Summary Researchers developed a.

Vagus Nerve and Cardiac Aging: New Heart Study

Vagus Nerve and Cardiac Aging: New Heart StudyKey Takeaways for Healthcare Professionals Preserving.

Cognitive Distraction From Conversation While Driving

Cognitive Distraction From Conversation While DrivingKey Takeaways (Quick Summary) Talking, not.

Fat-Regulating Enzyme Offers New Target for Obesity

Fat-Regulating Enzyme Offers New Target for ObesityKey Highlights (Quick Summary) Researchers identified.

Spatial Computing Explains How Brain Organizes Cognition

Spatial Computing Explains How Brain Organizes CognitionKey Takeaways (Quick Summary) MIT researchers.

Gestational Diabetes Risk Identified by Blood Metabolites

Gestational Diabetes Risk Identified by Blood MetabolitesKey Takeaways (Quick Summary for Clinicians).

Phage Therapy Study Reveals RNA-Based Infection Control

Phage Therapy Study Reveals RNA-Based Infection ControlKey Takeaways (Quick Summary) Researchers uncovered.

Pelvic Floor Disorders: Treatable Yet Often Ignored

Pelvic Floor Disorders: Treatable Yet Often IgnoredKey Takeaways (Quick Summary) Pelvic floor.

Urine-Based microRNA Aging Clock Predicts Biological Age

Urine-Based microRNA Aging Clock Predicts Biological AgeKey Takeaways (Quick Summary) Researchers developed.

Leave a Comment