A proper treatment for ocular infections is imperative because it dictates the prognosis. To obtain the best outcome, a systematic approach for ocular infections is essential.

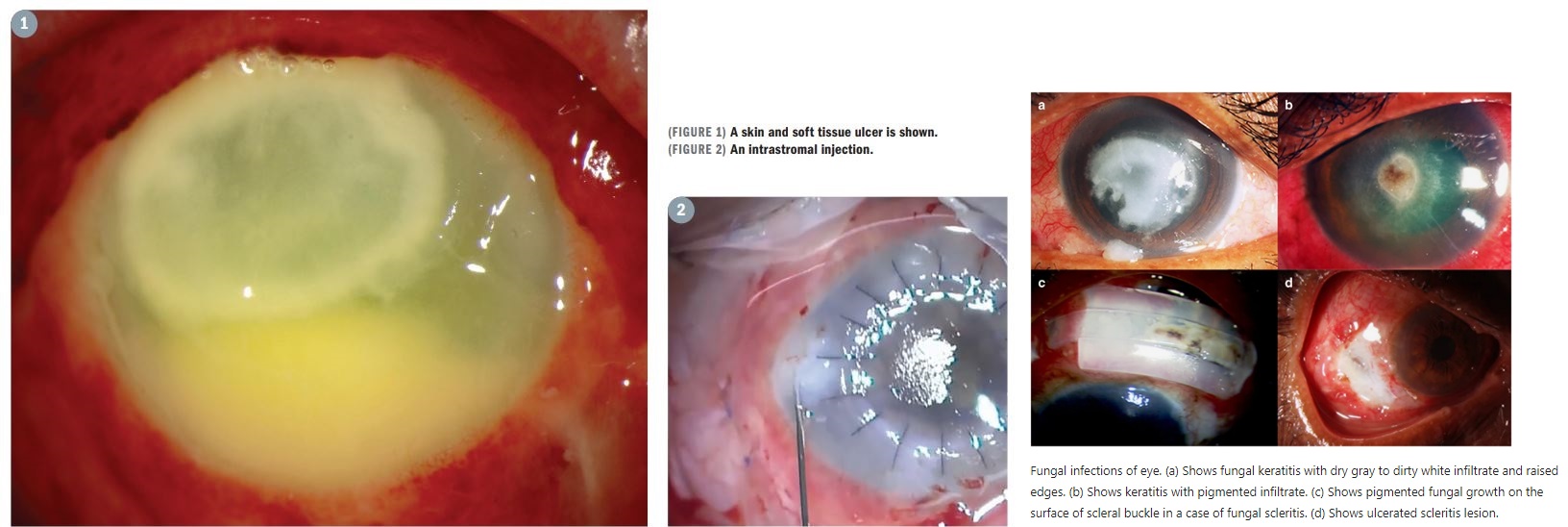

Identifying and treating ocular infections can be challenging. Ocular infections may share identical clinical result and be caused by different etiologic agents. The infection is usually named according to the ocular structures involved with the suffix “itis” meaning infectious or noninfectious inflammation.

The introduction of new classes of antibiotics during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s was considered to herald victory in the war against bacterial infections. However, the optimism proved premature, as a subsequent drought in new drug development accompanied by rapid development of bacterial resistance to existing agents created challenges for treatment success.

Commercially available options for treating ocular infections are limited as is the utility of many available agents because of microbial resistance or safety concerns. Treatment selection based on knowledge of the antimicrobial spectrum of available medications and compounding of systemic medications helps to address therapeutic challenges.

There are only a limited number of commercially available topical antibiotics, and natamycin ophthalmic suspension, 5% (Natacyn) is the only commercially available antifungal agent for ophthalmic use.

Thus, there is a very great need for new ocular antimicrobials, and hopefully there will be more activity in this area in the near future.

The Big Picture

Antibiotic resistance among ocular pathogens is particularly problematic for treating infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). For example, recent data show that over 90% of MRSA strains are resistant to erythromycin, which is used extensively to treat ocular infections.

Although MRSA is almost globally sensitive to trimethoprim, the antibiotic, unfortunately, has bacteriostatic rather than bactericidal activity. Emergence of antibiotic resistance among gram-negative ocular pathogens is also a concern.

Although resistance rates among gram-negative bacteria are generally lower than for MRSA, the resistant gram-negative pathogens are not only resistant to multiple antibiotics, but some are also extremely drug resistant or even pandrug resistant.

Gram-negative bacteria are still very sensitive to polymyxin B, and that makes topical polymyxin B sulfate-trimethoprim (Polytrim) an excellent topical option to use for infection prophylaxis, even if it is not a medication of choice for treatment.

Understanding The Resistance

Although no new classes of ocular antibiotics or antifungals have been introduced for many years, newer variations of existing classes and repurposed systemic medications are helping to meet therapeutic needs.

Besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension, 0.6% (Besivance), which is commercially available for ophthalmic use, represents the newest generation of ophthalmic fluoroquinolones and has not been used systemically.

Therefore, in theory, development of bacterial resistance to besifloxacin is less likely to occur, and in vitro data show that besifloxacin provides better coverage of various gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria relative to older fluoroquinolones.

In addition to traditional compounded topical medications such as fortified tobramycin, vancomycin, and the various cephalosporins, newer systemic antibiotics being compounded for topical use to treat resistant infections include linezolid (Zyvox) for vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus and MRSA, colistin for multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas infections, and imipenem for Nocardia.

Regarding antifungals, the introduction of voriconazole early in the 21st century generated excitement because it represented a less-toxic alternative to amphotericin B. However, voriconazole still has significant adverse effects when used systemically, and the topical formulation is less effective than natamycin for treating Fusarium infections.

Other newer antifungals being used for ocular infection include the echinocandins; caspofungin, 0.5%; and micafungin, 0.1%. These agents have shown good efficacy against resistant Candida and Aspergillus species, but they are also minimally effective against Fusarium and other filamentous fungi.

For treatment of amoebic infections, there are reports describing the use of oral miltefosine (Impavido) for Acanthamoeba keratitis. Miltefosine was approved in the United States for treatment of leishmaniasis in 2014.

Other Options

Antiseptics (ie, chlorhexidine and povidone-iodine) are bactericidal agents that are agnostic to bacterial sensitivity or resistance to traditional antibiotics because they act by destroying cell walls and intracellular contents.

By virtue of their mechanism of action, however, they are also toxic to normal ocular surface cells. Furthermore, antiseptic agents are less effective for eradicating fungal organisms, although they can have a role as an adjunct for treating difficult fungal infections.

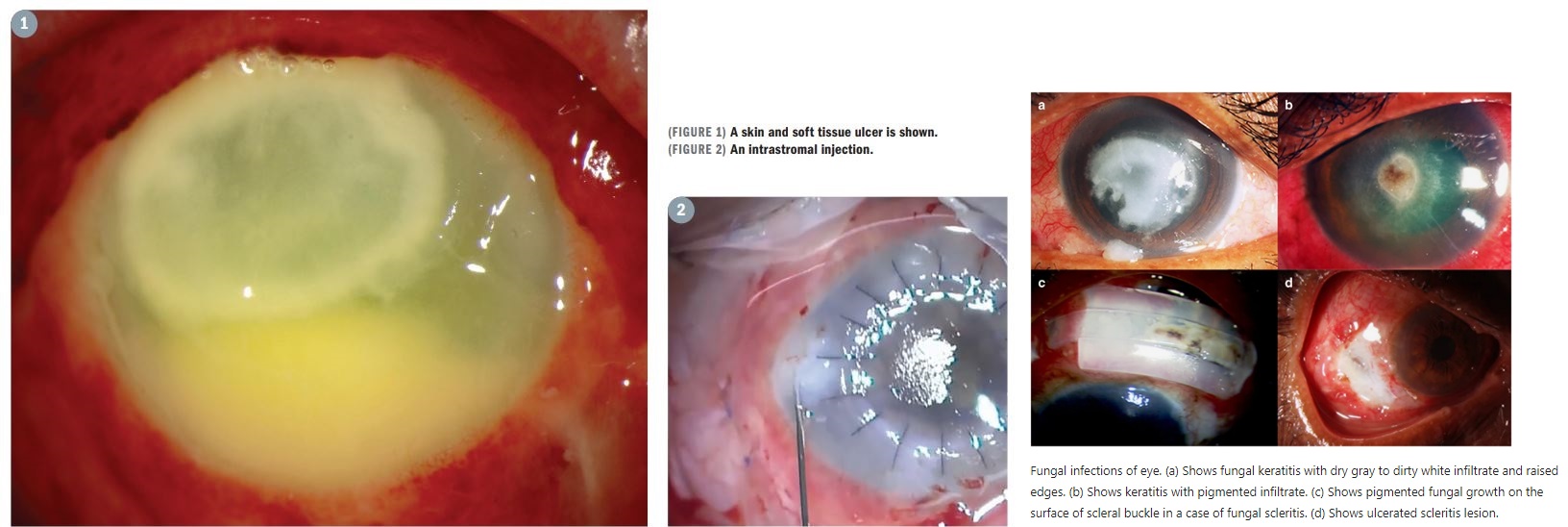

In the absence of new medications to treat challenging infections, there has been interest in delivering existing agents via alternative routes that could improve their bioavailability. Intrastromal injection of antifungal agents, usually amphotericin B or voriconazole, is representative of this strategy.

Typically, doctors use a 30-gauge or 32-gauge needle to make several intrastromal blebs surrounding the ulcer. This approach has been effective for treating deeper, difficult-to-treat infections.

more recommended stories

ChatGPT Excels in Medical Summaries, Lacks Field-Specific Relevance

ChatGPT Excels in Medical Summaries, Lacks Field-Specific RelevanceIn a recent study published in.

Study finds automated decision minimizes high-risk medicine combinations in ICU patients

Study finds automated decision minimizes high-risk medicine combinations in ICU patientsA multicenter study coordinated by Amsterdam.

Study Discovers Connection Between Omicron Infection and Brain Structure Changes in Men

Study Discovers Connection Between Omicron Infection and Brain Structure Changes in MenA recent study in the JAMA.

Advancing COPD Prognosis: Deep Learning Models

Advancing COPD Prognosis: Deep Learning ModelsResearchers conducted a meta-analysis in a.

4 in 1 Test for Swine Flu, COVID-19, RSV, and Influenza

4 in 1 Test for Swine Flu, COVID-19, RSV, and InfluenzaIn the United Kingdom, the first.

Innovative Zika Virus Defense: Needle-Free Vaccine Patch

Innovative Zika Virus Defense: Needle-Free Vaccine PatchTo protect individuals from the potentially.

Social Media Impact on Mental Health Treatment

Social Media Impact on Mental Health TreatmentAccording to research, social media might.

Unveiling the Impact of Whole Grain Consumption on Slowing Memory Decline in Black Populations

Unveiling the Impact of Whole Grain Consumption on Slowing Memory Decline in Black PopulationsConsuming a diet rich in whole.

$1 Cancer Treatment: Engineered Bacteria Breakthrough

$1 Cancer Treatment: Engineered Bacteria BreakthroughWhat if a single one-dollar dose.

Pfizer COVID Booster: Half-Dose, Reduced Side Effects

Pfizer COVID Booster: Half-Dose, Reduced Side EffectsIn a recent report in The.

Leave a Comment