The painful, genetic blood ailment sickle cell disease (SCD) may be treatable using stem cell gene therapy, according to new study that was just published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The results of a recent clinical trial, which were released on August 31 and which add to the body of evidence in favor of gene therapy as a treatment for sickle cell disease, which largely affects people of color, are encouraging.

According to the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there are around 100,000 Americans who have sickle cell disease. One in 365 Black kids born in the United States and one in 16,300 Hispanic newborns are affected by the illness, which can lead to a lifetime of agony, medical issues, and expenses.

The only available treatments up until recently were extensive bone marrow transplants from matched or sibling donors. However, other curative treatments are now in the works. One of three locations to enroll patients in the clinical trial testing a stem cell gene therapy to treat sickle cell disease was the University of Chicago Medicine Comer Children’s Hospital.

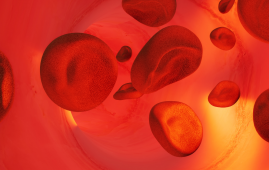

The trial involved editing particular genes in stem cells, which are the precursors to blood cells, obtained from each patient using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. The modifications boosted the cells’ ability to produce fetal hemoglobin (HbF), a protein that can replace sickled, unhealthy hemoglobin in the blood and shield against sickle cell disease consequences. The patients then received therapeutic infusions of their own modified cells.

The goal of the therapy was to broaden access to such a treatment by using CRISPR-Cas9 technology for the second time to treat this condition, targeting a novel genetic region and using cryopreserved stem cells for the first time. Lentiviruses, a type of virus frequently modified and used for gene editing that remain in the cell for a long time, have been employed in other gene therapy research for SCD. In stem cells modified using CRISPR-Cas9, there is no trace of foreign material.

Trial subjects who got the CRISPR-edited stem cells reported having fewer painful vaso-occlusive episodes, which happen when sickled red blood cells build up and blockarteries.

“The biggest take-home message is that there are now more potentially curative therapies for sickle cell disease than ever before that lie outside of using someone else’s stem cells, which can bring a host of other complications,” said James LaBelle, MD, Ph.D., director of the Pediatric Stem Cell and Cellular Therapy Program at UChicago Medicine and Comer Children’s Hospital and senior author of the study.

“Especially in the last 10 years, we’ve learned about what to do and what not to do when treating these patients. There’s been a great deal of effort towards offering patients different types of transplants with decreased toxicities, and now gene therapy rounds out the set of available treatments, so every patient with sickle cell disease can get some sort of curative therapy if needed. At UChicago Medicine, we’ve built infrastructure to support new approaches to sickle cell disease treatment and to bring additional gene therapies for other diseases.

Curative treatments for conditions like sickle cell disease are increasingly a possibility as the scientific community works to improve and broaden the uses of gene therapy. Even though there is still a long way to go and more research and long-term monitoring are required, this study offers a hopeful window into the possibility of successful genetic therapies in the future.

LaBelle emphasized the significance of the study’s addition to the expanding body of information demonstrating the viability of gene therapy as a treatment for sickle cell disease in the broader context of therapeutic development. This year, the FDA must still approve two further gene treatments for the illness.

“The data from this trial supports bringing on similar gene therapies for sickle cell disease and for other bone marrow-derived diseases. If we didn’t have this data, those wouldn’t move forward,” he said.

more recommended stories

Microplastic Exposure and Parkinson’s Disease Risk

Microplastic Exposure and Parkinson’s Disease RiskKey Takeaways Microplastics and nanoplastics (MPs/NPs).

Sickle Cell Gene Therapy Access Expands Globally

Sickle Cell Gene Therapy Access Expands GloballyKey Summary Caring Cross and Boston.

Reducing Alcohol Consumption Could Lower Cancer Deaths

Reducing Alcohol Consumption Could Lower Cancer DeathsKey Takeaways (At a Glance) Long-term.

NeuroBridge AI Tool for Autism Communication Training

NeuroBridge AI Tool for Autism Communication TrainingKey Takeaways Tufts researchers developed NeuroBridge,.

Population Genomic Screening for Early Disease Risk

Population Genomic Screening for Early Disease RiskKey Takeaways at a Glance Population.

Type 2 Diabetes Risk Identified by Blood Metabolites

Type 2 Diabetes Risk Identified by Blood MetabolitesKey Takeaways (Quick Summary) Researchers identified.

Microglia Neuroinflammation in Binge Drinking

Microglia Neuroinflammation in Binge DrinkingKey Takeaways (Quick Summary for HCPs).

Durvalumab in Small Cell Lung Cancer: Survival vs Cost

Durvalumab in Small Cell Lung Cancer: Survival vs CostKey Points at a Glance Durvalumab.

Precision Oncology with Personalized Cancer Drug Therapy

Precision Oncology with Personalized Cancer Drug TherapyKey Takeaways UC San Diego’s I-PREDICT.

Iron Deficiency vs Iron Overload in Parkinson’s Disease

Iron Deficiency vs Iron Overload in Parkinson’s DiseaseKey Takeaways (Quick Summary for HCPs).

Leave a Comment