A research of children and adolescents with diabetes conducted by the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center found that so-called autonomous artificial intelligence (AI) diabetic eye exams considerably boost completion rates of screenings meant to avoid potentially blinding diabetes eye disorders (DED). During the exam, images of the backs of the eyes are captured without dilation, and AI is employed to deliver an immediate result.

The AI-driven technology used in the exams, according to the study, may eliminate “care gaps” among racial and ethnic minority kids with diabetes, populations with historically higher incidence of DED and poorer access to or adherence with frequent screening for eye impairment.

Investigators studied diabetic eye exam completion rates in adults under the age of 21 with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in a publication published Jan. 11 in Nature Communications, and discovered that 100% of patients who attended AI exams completed the eye evaluation.

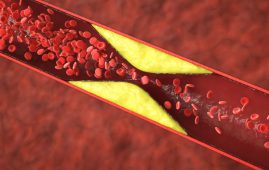

DED is most commonly associated with diabetic retinopathy, a potentially blinding complication of diabetes that occurs when poorly regulated sugar levels cause an overgrowth of, or damage to, blood vessels and nerve tissues in the light-sensitive retina at the rear of the eye. According to the study’s authors, retinopathy affects between 4% and 9% of type 1 diabetes kids and 4% to 15% of type 2 diabetic youth. According to the American Diabetes Association, approximately 238,000 children, adolescents, and young people under the age of 20 have diabetes. Frequent DED screenings aid in early discovery and treatment, as well as preventing DED progression.

Diabetes specialists and eye doctors generally recommend annual screenings, which typically require a separate visit to an eye care provider, such as an optometrist or ophthalmologist, and the use of drops to dilate the pupil so that a clear view of the retina can be seen through specialized instruments. However, research suggest that approximately 35% to 72% of diabetic kids receive recommended checkups, with much greater rates of care gap among minority and impoverished youth. Previous research has found that hurdles to screenings include a lack of understanding about the necessity for screens, as well as inconvenience, a lack of time, access to specialists, and transportation.

Previously, Risa Wolf, M.D., a pediatric endocrinologist at Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, and her colleagues discovered that autonomous AI screening using webcams produces data that allow accurate DED diagnosis.

The new study enrolled 164 patients between November 24, 2021, and June 6, 2022, ranging in age from 8 to 21 years and all from the Johns Hopkins Pediatric Diabetes Center. 58% were female, and 41% belonged to a minority group (35% Black, 6% Hispanic). 47% of participants had Medicaid coverage. The subjects were divided into two groups at random. A total of 83 patients were given standard screening instructions and care before being referred to an optometrist or ophthalmologist for an eye exam. A second group of 81 patients had a five-to-ten-minute autonomous AI system diabetic eye exam during a visit to an endocrinologist (the specialists who normally care for persons with diabetes), and their results were provided at the same time.

According to Wolf, the AI system takes four photographs of the eye without dilatation and then runs the photos through an algorithm that evaluates the presence or absence of diabetic retinopathy. If it is found, a referral to an eye doctor is issued for further evaluation. “You’re good for the year, and you just saved yourself time,” she says if it’s missing.

Researchers discovered that 100% of patients in the group given the autonomous AI screening completed their eye test on the same day, whereas 22% of patients in the second group completed an eye check with an optometrist or ophthalmologist within six months. The researchers discovered no statistical differences in whether participants in the second group booked the separate screening with an eye doctor based on race, gender, or socioeconomic position.

The researchers also discovered that DED was present in 25 out of 81 subjects, or 31%, in the autonomous AI group.

“With AI technology, more people can get screened, which could then help identify more people who need follow-up evaluation,” Wolf said. “If we can offer this more conveniently at the point of care with their diabetes doctor, then we can also potentially improve health equity, and prevent the progression of diabetic eye disease.”

The researchers warn that the autonomous AI utilized in their study has not been authorized by the US Food and Drug Administration for people under the age of 21. They also claim that one potential source of bias in the study was that some of the participants were already familiar with autonomous AI diabetic eye exams from a previous study, and thus were more inclined to participate in the present one.

Johns Hopkins study authors include Alvin Liu, Anum Zehra, Lee Bromberger, Dhruva Patel, Ajaykarthik Ananthakrishnan, Elizabeth Brown, Laura Prichett, and Harold Lehmann, in addition to Wolf. Roomasa Channa of the University of Wisconsin and Michael D. Abramoff of the University of Iowa are the other authors.

more recommended stories

Caffeine and SIDS: A New Prevention Theory

Caffeine and SIDS: A New Prevention TheoryFor the first time in decades,.

Microbial Metabolites Reveal Health Insights

Microbial Metabolites Reveal Health InsightsThe human body is not just.

Reelin and Cocaine Addiction: A Breakthrough Study

Reelin and Cocaine Addiction: A Breakthrough StudyA groundbreaking study from the University.

Preeclampsia and Stroke Risk: Long-Term Effects

Preeclampsia and Stroke Risk: Long-Term EffectsPreeclampsia (PE) – a hypertensive disorder.

Statins and Depression: No Added Benefit

Statins and Depression: No Added BenefitWhat Are Statins Used For? Statins.

Azithromycin Resistance Rises After Mass Treatment

Azithromycin Resistance Rises After Mass TreatmentMass drug administration (MDA) of azithromycin.

Generative AI in Health Campaigns: A Game-Changer

Generative AI in Health Campaigns: A Game-ChangerMass media campaigns have long been.

Molecular Stress in Aging Neurons Explained

Molecular Stress in Aging Neurons ExplainedAs the population ages, scientists are.

Higher BMI and Hypothyroidism Risk Study

Higher BMI and Hypothyroidism Risk StudyA major longitudinal study from Canada.

Therapeutic Plasma Exchange Reduces Biological Age

Therapeutic Plasma Exchange Reduces Biological AgeTherapeutic plasma exchange (TPE), especially when.

Leave a Comment