A team of scientists from Gladstone Institutes was motivated to investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying neurodegeneration caused by traumatic brain injuries and, more significantly, how to interrupt this process to avert long-term harm, given the conspicuous lack of therapies for this prevalent disorder.

We set out to address the fundamental question of exactly what happens in the brain after injury to ignite the damaging process that destroys neurons,” states Gladstone Institutes’ Jae Kyu Ryu, PhD, a scientific program leader in Katerina Akassoglou’s lab.

“We knew that a specific blood protein, fibrin, was present in the brain after traumatic brain injury, but we didn’t know until now that it plays a causative role in brain damage after injury,” says Ryu, who led the study that appears in the Journal of Neuroinflammation.

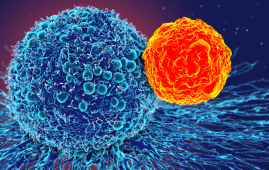

For an extended period, Ryu and associates in Akassoglou’s laboratory have studied the mechanism by which blood leaks into the brain causing neurologic illnesses. This involves subverting the immune system of the brain and causing a series of detrimental, frequently irreversible consequences. The offending protein is fibrin, which typically aids in blood coagulation.

For more comprehensive Neurology insights explore Global Neurology Summit 2024

Across many neurological diseases, toxic immune responses in the brain are triggered by blood leaks and drive neurodegeneration. Neutralizing the toxic immune responses in the brain paves the way to new therapies for neurological diseases.” Katerina Akassoglou, senior investigator at Gladstone and director of the Center for Neurovascular Brain Immunology at Gladstone and UCSF

Abnormal leaks in the blood-brain barrier allow fibrin to infiltrate into areas crucial for cognitive and motor processes, leading to neurodegeneration in disorders like multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s. In this instance, however, blood seeps into the brain as a result of the traumatic brain injury itself. For the first time, the new study demonstrated that fibrin is the cause of harmful inflammation, the degeneration of healthy immune cells, and the release of neurodegenerative toxins.

“It became clear that fibrin is activating these immune cells,” Ryu says. “We realized that we could prevent the toxic effects if we could block fibrin, but we had to do it in a precise way.”

Using genetic methods, the team was able to inhibit fibrin from activating immune cells without compromising the protein’s useful blood-clotting properties. This is particularly important in cases of severe brain injuries since individuals who were on anticoagulant drugs before their injury have been reported to experience significant bleeding into the brain.

A therapeutic monoclonal antibody that only targets the inflammatory characteristics of fibrin and has no negative effects on blood coagulation was previously created by Akassoglou’s team. In mice, this fibrin-targeting immunotherapy protects against Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis. Phase 1 safety clinical trials for Therini Bio’s humanized variant of this first-in-class fibrin immunotherapy are currently underway.

“It’s exciting to have a therapeutic option to neutralize blood toxicity in neurologic diseases,” Ryu says. “Future studies are needed to test the effects of the fibrin immunotherapy in traumatic brain injury.”

“This study identifies a potential new strategy to diminish the devastating impacts of brain injuries,” says Lennart Mucke, MD, director of the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease. “Brain injuries can have profound effects on a person’s cognitive abilities, emotional health, and motor skills, touching every part of their life. It will be interesting to explore whether blocking the disease-promoting effects of fibrin can improve the outcome of brain surgeries and reduce disability when implemented after traumatic brain injuries have occurred.”

For more information: Fibrin promotes oxidative stress and neuronal loss in traumatic brain injury via innate immune activation, Journal of Neuroinflammation, doi.org/10.1186/s12974-024-03092-w

more recommended stories

T-bet and the Genetic Control of Memory B Cell Differentiation

T-bet and the Genetic Control of Memory B Cell DifferentiationIn a major advancement in immunology,.

Ultra-Processed Foods May Harm Brain Health in Children

Ultra-Processed Foods May Harm Brain Health in ChildrenUltra-Processed Foods Linked to Cognitive and.

Parkinson’s Disease Care Advances with Weekly Injectable

Parkinson’s Disease Care Advances with Weekly InjectableA new weekly injectable formulation of.

Brain’s Biological Age Emerges as Key Health Risk Indicator

Brain’s Biological Age Emerges as Key Health Risk IndicatorClinical Significance of Brain Age in.

Children’s Health in the United States is Declining!

Children’s Health in the United States is Declining!Summary: A comprehensive analysis of U.S..

Autoimmune Disorders: ADA2 as a Therapeutic Target

Autoimmune Disorders: ADA2 as a Therapeutic TargetAdenosine deaminase 2 (ADA2) has emerged.

Is Prediabetes Reversible through Exercise?

Is Prediabetes Reversible through Exercise?150 Minutes of Weekly Exercise May.

New Blood Cancer Model Unveils Drug Resistance

New Blood Cancer Model Unveils Drug ResistanceNew Lab Model Reveals Gene Mutation.

Healthy Habits Slash Diverticulitis Risk in Half: Clinical Insights

Healthy Habits Slash Diverticulitis Risk in Half: Clinical InsightsHealthy Habits Slash Diverticulitis Risk in.

Caffeine and SIDS: A New Prevention Theory

Caffeine and SIDS: A New Prevention TheoryFor the first time in decades,.

Leave a Comment