Autologous conditioned serum (ACS), a biologic therapy utilized by famous athletes to treat arthritis and sports injuries, has also been shown to help with neurological pain induced by chemotherapy or diabetes.

In a rodent investigation, Duke Health researchers discovered that a spinal injection of the conditioned serum relieved limb pain for far longer than standard analgesics. They also demonstrated that the long-term pain reduction is caused by a pathway other than the anti-inflammatory effects traditionally attributed to ACS—an finding that potentially improve and expand the therapy’s use.

The findings are published online in the journal Brain, Behavior, and Immunity.

“This treatment just seemed to be more effective and longer lasting than other biologic therapies,” said lead author Thomas Buchheit, M.D., associate professor in Duke’s Department of Anesthesiology and director of the Duke Regenerative Pain Therapies Program.

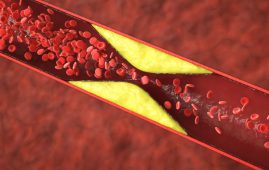

ACS is made from a person’s own blood, which is centrifuged to eliminate blood cells and concentrate anti-inflammatory proteins. While not FDA authorized, the therapy is available at Duke and a few other centers in the United States, and has long been praised by athletes who have had cartilage injections.

Buchheit and co-senior author Ru-Rong Ji, Ph.D., began working together with ACS to better understand the long-term determinants of pain relief. Ji is a professor at Duke with expertise in the molecular and cellular factors underlying pain; he is also the director of the Center for Translational Pain Medicine.

The team also drew on the knowledge of co-senior author Tony Jun Huang, Ph.D., professor of Mechanical Engineering & Material Science, who studies micro-particles in fluids for biological diagnostics and therapies.

The Duke researchers employed human, rat, and mouse ACS fluid to investigate its efficacy as a neuropathy therapeutic. The serums were administered into mice and rats following treatment with the chemotherapeutic medication paclitaxel, which is used to treat breast, ovarian, and lung malignancies. Paclitaxel’s most prevalent side effect is numbness and tingling in the hands and feet.

Not only did the therapy relieve the animals’ nerve discomfort, but it also lasted many weeks—far longer than the hours or days supplied by standard pain medications.

“That prompted us to examine what was driving this long-lasting effect, because it could not be explained by the typical anti-inflammatory properties that we associate with ACS,” Buchheit said.

The quantity of growth proteins and anti-inflammatory cytokines identified in the serum has been substantially linked to the effects of ACS. Cytokines are signaling proteins that aid in the regulation of inflammation. However, these proteins would only produce short-term benefits, rather than the long-term benefits demonstrated in the study and realized in real-world clinical circumstances.

Exosomes, according to the Duke researchers, appear to be the component that gives ACS its endurance. These tiny vesicles contain a slew of anti-inflammatory chemicals, including micro-RNAs, and they become highly activated during the ACS conditioning and incubation phase.

“Our finding is that exosomes—small packages of information that cells such as immune cells share—are responsible for the long-term pain-relieving effects of ACS,” Ji said. “By describing this newly identified mechanism for how ACS provides extended pain relief, we can explore a number of additional therapeutic uses. We are greatly interested in continuing our work to investigate exosome profiles in ACS to further define the mechanisms behind this pain relief therapy.”

more recommended stories

Caffeine and SIDS: A New Prevention Theory

Caffeine and SIDS: A New Prevention TheoryFor the first time in decades,.

Microbial Metabolites Reveal Health Insights

Microbial Metabolites Reveal Health InsightsThe human body is not just.

Reelin and Cocaine Addiction: A Breakthrough Study

Reelin and Cocaine Addiction: A Breakthrough StudyA groundbreaking study from the University.

Preeclampsia and Stroke Risk: Long-Term Effects

Preeclampsia and Stroke Risk: Long-Term EffectsPreeclampsia (PE) – a hypertensive disorder.

Statins and Depression: No Added Benefit

Statins and Depression: No Added BenefitWhat Are Statins Used For? Statins.

Azithromycin Resistance Rises After Mass Treatment

Azithromycin Resistance Rises After Mass TreatmentMass drug administration (MDA) of azithromycin.

Generative AI in Health Campaigns: A Game-Changer

Generative AI in Health Campaigns: A Game-ChangerMass media campaigns have long been.

Molecular Stress in Aging Neurons Explained

Molecular Stress in Aging Neurons ExplainedAs the population ages, scientists are.

Higher BMI and Hypothyroidism Risk Study

Higher BMI and Hypothyroidism Risk StudyA major longitudinal study from Canada.

Therapeutic Plasma Exchange Reduces Biological Age

Therapeutic Plasma Exchange Reduces Biological AgeTherapeutic plasma exchange (TPE), especially when.

Leave a Comment