The inability of the most potent chemotherapy to penetrate the blood-brain barrier and reach the aggressive brain tumor has been a key hindrance to treating the lethal brain cancer glioblastoma.

Northwestern Medicine researchers have now published the findings of the first-in-human clinical trial in which they used a novel, skull-implantable ultrasound device to open the blood-brain barrier and repeatedly permeate large, critical regions of the human brain to deliver chemotherapy that was injected intravenously.

The four-minute treatment to open the blood-brain barrier is done while the patient is conscious, and patients are discharged after a few hours. The findings suggest that the treatment is safe and well tolerated, with some patients receiving up to six cycles.

This rise was observed with two separate strong chemotherapy medications, paclitaxel, and carboplatin. The medications are not utilized to treat these patients since they do not normally penetrate the blood-brain barrier.

Furthermore, this is the first study to describe the rate at which the blood-brain barrier closes after sonication. According to the researchers, the majority of blood-brain barrier restoration occurs within the first 30 to 60 minutes after sonication. The findings will allow the authors to optimize the sequence of medication delivery and ultrasonic activation to enhance drug penetration into the human brain.

“This is potentially a huge advance for glioblastoma patients,” said lead investigator Dr. Adam Sonabend, an associate professor of neurological surgery at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and a Northwestern Medicine neurosurgeon.

Temozolomide, the current chemotherapy used for glioblastoma, does cross the blood-brain barrier, but is a weak drug, Sonabend said.

The paper will be published May 2 in The Lancet Oncology.

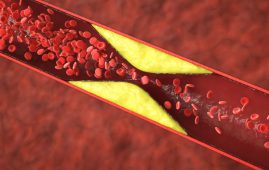

The blood-brain barrier is a tiny structure that protects the brain from the vast majority of medications that circulate in the blood. As a result, the pharmacological repertoire available for treating brain illnesses is quite limited. Most medications that are successful for cancer elsewhere in the body cannot be used to treat patients with brain cancer because they do not penetrate the blood-brain barrier. Drug repurposing for brain disease and cancer requires drug delivery to the brain.

Previously, studies that injected paclitaxel directly into the brains of patients with similar tumors found encouraging results, but the direct injection was associated with damage such as brain inflammation and meningitis, according to Sonabend.

The researchers discovered that the use of ultrasound and microbubble-based opening of the blood-brain barrier is transitory and that most of the blood-brain barrier integrity is restored in humans within one hour of this technique.

“There is a critical time window after sonification when the brain is permeable to drugs circulating in the bloodstream,” Sonabend said.

Previous human studies indicated that the blood-brain barrier is entirely restored 24 hours after brain sonication, and the field considered that the blood-brain barrier is open for the first six hours or so based on animal studies. According to the Northwestern study, this time frame may be reduced.

The study also reveals that a revolutionary skull-implantable grid of nine ultrasound emitters produced by the French biotech company Carthera opens the blood-brain barrier in a volume of the brain nine times greater than the initial device (a modest single-ultrasound emitter implant). This is significant because, in order for this method to be effective, a vast section of the brain close to the cavity that remains in the brain following glioblastoma removal must be covered.

The study’s findings constitute the foundation for the scientists’ ongoing phase 2 clinical trial for patients with recurrent glioblastoma. The goal of the trial, in which participants get a combination of paclitaxel and carboplatin given to their brain via ultrasound, is to see if this treatment increases the patients’ chances of survival. Other cancers use a combination of these two drugs, which is why they are being combined in the phase 2 trial.

Patients in phase 1 clinical study reported in this paper received surgery for tumor excision and ultrasonography device implantation. They began treatment a few weeks after the implantation. The researchers increased the paclitaxel dose provided every three weeks, along with the associated ultrasound-based blood-brain barrier opening. During surgery, studies were conducted on subsets of patients to investigate the effect of this ultrasound device on drug concentrations. The blood-brain barrier was seen and mapped in the operating room using fluorescein dye and MRI was collected following ultrasonic therapy.

“While we have focused on brain cancer (for which there are approximately 30,000 gliomas in the U.S.), this opens the door to investigate novel drug-based treatments for millions of patients who suffer from various brain diseases,” Sonabend said.

more recommended stories

Caffeine and SIDS: A New Prevention Theory

Caffeine and SIDS: A New Prevention TheoryFor the first time in decades,.

Microbial Metabolites Reveal Health Insights

Microbial Metabolites Reveal Health InsightsThe human body is not just.

Reelin and Cocaine Addiction: A Breakthrough Study

Reelin and Cocaine Addiction: A Breakthrough StudyA groundbreaking study from the University.

Preeclampsia and Stroke Risk: Long-Term Effects

Preeclampsia and Stroke Risk: Long-Term EffectsPreeclampsia (PE) – a hypertensive disorder.

Statins and Depression: No Added Benefit

Statins and Depression: No Added BenefitWhat Are Statins Used For? Statins.

Azithromycin Resistance Rises After Mass Treatment

Azithromycin Resistance Rises After Mass TreatmentMass drug administration (MDA) of azithromycin.

Generative AI in Health Campaigns: A Game-Changer

Generative AI in Health Campaigns: A Game-ChangerMass media campaigns have long been.

Molecular Stress in Aging Neurons Explained

Molecular Stress in Aging Neurons ExplainedAs the population ages, scientists are.

Higher BMI and Hypothyroidism Risk Study

Higher BMI and Hypothyroidism Risk StudyA major longitudinal study from Canada.

Therapeutic Plasma Exchange Reduces Biological Age

Therapeutic Plasma Exchange Reduces Biological AgeTherapeutic plasma exchange (TPE), especially when.

Leave a Comment