A new study led by UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers found that astronauts who spent up to six months aboard the International Space Station (ISS) experienced no loss of muscle mass or function in their ventricles – the pumping chambers of the heart. The findings, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, could have significant consequences for treating disorders in which gravity plays a role, as well as for planning lengthier expeditions, such as missions to Mars.

“Our study shows that, remarkably, what we are doing in space to preserve heart function and morphology is pretty effective,” said senior author Benjamin Levine, M.D., Professor of Internal Medicine in the Division of Cardiology at UT Southwestern who holds a Distinguished Professorship in Exercise Sciences. He is the founding Director of the Institute for Exercise and Environmental Medicine at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas, where he also holds the S. Finley Ewing Chair for Wellness and the Harry S. Moss Heart Chair for Cardiovascular Research.

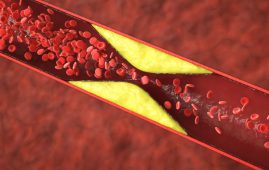

Researchers have known that astronauts returning to Earth often experience a considerable drop in blood pressure since the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) began sending humans into space in the early 1960s. Although various variables are to blame, Dr. Levine said that remodeling of the heart in response to microgravity circumstances is a major culprit. Astronauts, like those on bed rest, do not work as hard in space as they do on Earth because they are not counteracting the effects of gravity. As a result, their cardiac muscle mass reduces by 1% per week on average, and the volume of blood held by the heart diminishes as well. Both have a substantial impact on heart function.

Although astronauts on the International Space Station exercise for roughly two hours every day, it is unknown whether this training can counteract the consequences of lengthy time in zero gravity.

Dr. Levine and his colleagues gathered data on 13 astronauts who spent an average of 155 days on the International Space Station between 2009 and 2013. Before, during, and after each astronaut’s flight, the researchers assessed blood pressure and computed stroke volume (blood pumped every beat) and cardiac output (blood flow per minute). They also did cardiac MRI scans to analyze heart anatomy two months before spaceflight, three days after their return to Earth, and three weeks later. The astronauts undertook regular exercise regimes that included both strength training and aerobic components both before and during their missions.

The results revealed that astronauts’ blood pressure dropped considerably in space compared to on Earth. Similarly, the amount of labor their hearts did fell by roughly 12%. However, neither the left nor right ventricles lost muscle mass, and the amount of blood pumped out of the heart remained roughly the same as before the flight.

“There’s nothing magical about space and microgravity. The heart is quite plastic and responds to changes in physical activity,” Dr. Levine noted. “It’s reassuring that the training astronauts are doing in space can protect their hearts from the risks inherent to spaceflight, even on extended missions.”

Dr. Levine points out that earlier research has showed atria dilatation in these same astronauts, raising the idea that they may be at risk for atrial fibrillation during longer-duration missions. This is the focus of his study team’s current ISS studies.

Similarly, he added, specific exercise regimens can help patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, a condition that causes symptoms like increased heart rate, dizziness, and fatigue when patients move from lying down to standing up, as well as a variety of other gravity-related conditions.

Shigeki Shibata, M.D., Ph.D., Instructor of Internal Medicine; Shuaib Abdullah, M.D., Associate Professor of Internal Medicine; and Denis Wakeham, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Researcher are other UTSW researchers that contributed to this study.

more recommended stories

New Blood Cancer Model Unveils Drug Resistance

New Blood Cancer Model Unveils Drug ResistanceNew Lab Model Reveals Gene Mutation.

Healthy Habits Slash Diverticulitis Risk in Half: Clinical Insights

Healthy Habits Slash Diverticulitis Risk in Half: Clinical InsightsHealthy Habits Slash Diverticulitis Risk in.

Caffeine and SIDS: A New Prevention Theory

Caffeine and SIDS: A New Prevention TheoryFor the first time in decades,.

Microbial Metabolites Reveal Health Insights

Microbial Metabolites Reveal Health InsightsThe human body is not just.

Reelin and Cocaine Addiction: A Breakthrough Study

Reelin and Cocaine Addiction: A Breakthrough StudyA groundbreaking study from the University.

Preeclampsia and Stroke Risk: Long-Term Effects

Preeclampsia and Stroke Risk: Long-Term EffectsPreeclampsia (PE) – a hypertensive disorder.

Statins and Depression: No Added Benefit

Statins and Depression: No Added BenefitWhat Are Statins Used For? Statins.

Azithromycin Resistance Rises After Mass Treatment

Azithromycin Resistance Rises After Mass TreatmentMass drug administration (MDA) of azithromycin.

Generative AI in Health Campaigns: A Game-Changer

Generative AI in Health Campaigns: A Game-ChangerMass media campaigns have long been.

Molecular Stress in Aging Neurons Explained

Molecular Stress in Aging Neurons ExplainedAs the population ages, scientists are.

Leave a Comment