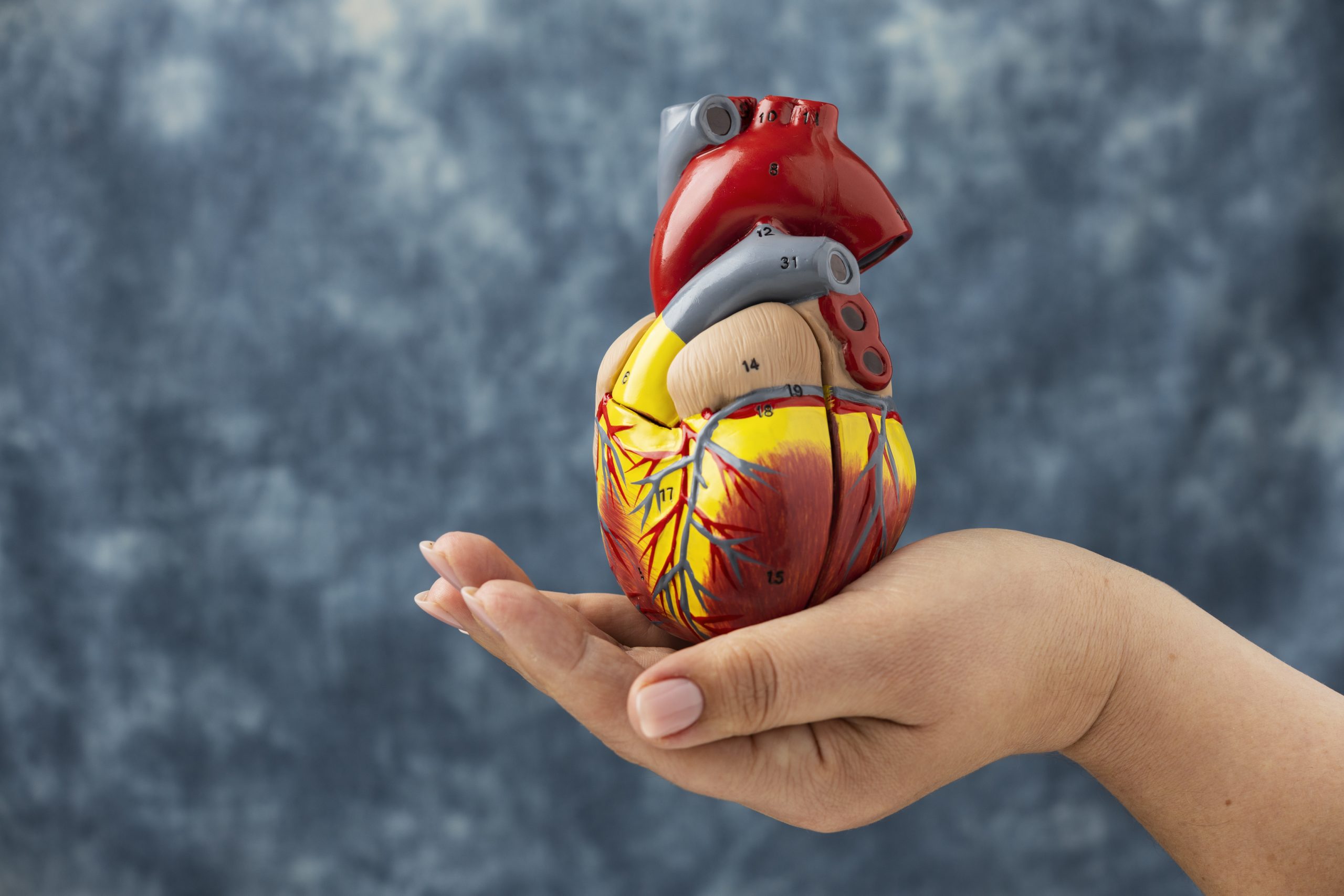

Stanford Medicine surgeons transplanted a heart while it was beating using an organ from a donor who died from cardiac arrest—the first time a beating-heart transplant has been accomplished. Initially conducted in October by Joseph Woo, MD, professor and chair of cardiothoracic surgery, and his team, the method has subsequently been employed in adult and pediatric patients five times by Stanford Medicine surgeons.

Because stopping the heart before implantation can harm the cardiac tissue, keeping it beating during transplantation protects the organ from further harm. “This can be revolutionary,” said Woo, the senior author of a study describing the procedure that was published in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery Techniques (JTCVS Techniques) in March. “It’s an exciting time for our entire department. This is a big team of very creative individuals that are willing to push the limits of modern technology and health care.”

In a country where 3,500 people are waiting for a heart transplant, expanding the pool of healthy donated organs is critical.

Brain death donors have historically made up the majority of heart transplants because it is easier to keep the organ stable and healthy in people who have been kept on life support prior to procurement. However, with demand outstripping supply, the medical community has been pushed to seek out more novel approaches.

Recent technological breakthroughs have enabled more successful beating-heart transplant from donors who died of cardiac or circulatory death, in which the heart had already stopped once, either naturally or as a result of being removed from life support.

Although such operations increase the number of accessible hearts for beating-heart transplants, the outcomes for recipients are lower.

Traditionally, these hearts have been stopped twice: once after death and again just before transplantation, after spending time linked up to a machine that perfuses them with oxygenated blood.

“Stopping the heart a second time, just before transplanting, induces more injury,” Woo said. “I asked, ‘Why can’t we sew it in while it is still beating?'”

The Stanford team believed that avoiding a second stoppage of the muscle would improve the quality of the donated heart, but figuring out how presented a challenge.

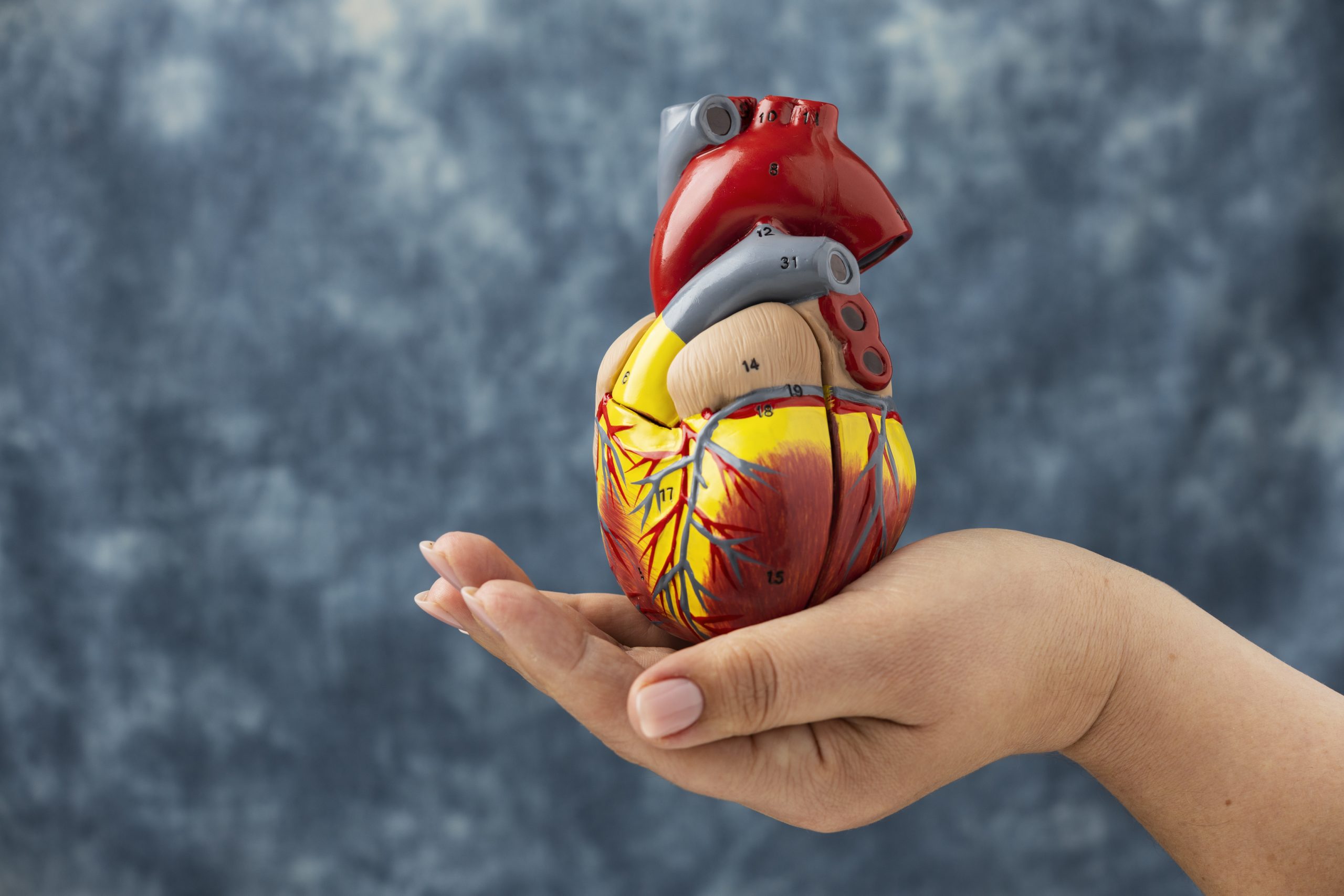

“It took a little boldness—because it’s a challenging, technical thing to do,” said Aravind Krishnan, MD, cardiothoracic surgery resident and the lead author of the paper describing the team’s findings.

Adults have also been treated using the procedure by John MacArthur, MD, assistant professor of cardiothoracic surgery, and Brandon Guenthart, MD, clinical assistant professor of cardiothoracic surgery. The first pediatric case was just performed by Michael Ma, MD, assistant professor of cardiothoracic surgery.

“By showing that it’s translatable it means it can change the entire community,” said Woo, the Norman E. Shumway Professor of cardiothoracic surgery.

Added Guenthart, “There’s excitement around the clinical aspect of it. We’re doing a lot of work in the lab to study it further and take it beyond what we’re doing now.”

The heart is stopped, retrieved from the deceased donor, and transported on ice to the transplantation site in brain-death donor transplants. Although it can take a long time to reawaken the recipient’s heart, it has only been halted once.

Organs recovered from a deceased donor, on the other hand, suffer from some degree of oxygen deprivation after the heart stops pumping before procurement can begin. Furthermore, studies have indicated that a lengthy period of no blood circulation in the heart degrades its performance following transplantation and reduces survival results.

This is why, rather than being placed on ice, those organs require the assistance of a perfusion machine.

While being moved, the organ preservation device—a relatively recent invention known as a “heart in a box”—restarts the heart and perfuses it with warm, oxygenated blood.

The Stanford patients had better implantation outcomes, leaving the hospital earlier than typical because the heart and its new host meshed more quickly.

“We thought that stopping the heart a second time was enough to weaken it,” MacArthur said. “Keeping the heart beating really seems to make a difference in heart strength with less time spent on the heart-lung machine.”

Ma, who used the beating-heart transplant procedure on the first pediatric patient earlier this month, said the gains on the front end—a continuous function of the organ leading to a shorter time spent in the hospital by the recipient—are immediate. And improvement in long-term outcomes for the organ and its new host is inevitable.

“We won’t be able to prove that for a long time, but there are enumerable benefits from this technique,” he said. “I was beyond excited to use this procedure pioneered by Joe and his team. It was a really rewarding experience.”

Woo and surgical team members Chawannuch Ruaengsri, MD, clinical assistant professor of cardiothoracic surgery, Krishnan, and Patpilai Kasinpila, MD, resident in cardiothoracic surgery performed the first beating heart transplant, which lasted four hours.

On that October day, the Stanford Health Care team was prepared to receive a heart obtained from a cardiac-death donor and transported in a box.

The heart was swiftly transferred to a cardiopulmonary bypass machine, which was already maintaining the patient. The machine, which circulates blood and oxygen throughout the body, guaranteed that warm blood flowed continuously. Woo then began the difficult task of stitching a beating heart into the recipient.

Krishnan said the team took comfort in knowing the machine was there as a backup if it proved too difficult. But it didn’t, and the Stanford Health Care team looked on as the heart kept its rhythm.

“It was beating so well,” Ruaengsri said.

All six patients are doing well. And the department is excited about continuing to push the boundaries of what’s possible.

“In order to do this, we had to challenge dogma,” said Woo, whose predecessor Norman E. Shumway performed the first adult heart transplant in the U.S. in 1968 at Stanford Hospital. “That’s how innovations occur.”

Added Guenthart, “We’re looking into ways of never having to stop the heart—that’s the next step.”

more recommended stories

New Blood Cancer Model Unveils Drug Resistance

New Blood Cancer Model Unveils Drug ResistanceNew Lab Model Reveals Gene Mutation.

Osteoarthritis Genetics Study Uncovers New Treatment Hope

Osteoarthritis Genetics Study Uncovers New Treatment HopeOsteoarthritis- the world’s leading cause of.

Antibody Breakthrough in Whooping Cough Vaccine

Antibody Breakthrough in Whooping Cough VaccineWhooping cough vaccine development is entering.

Scientists Unveil Next-Gen Eye-Tracking with Unmatched Precision

Scientists Unveil Next-Gen Eye-Tracking with Unmatched PrecisionEye-tracking technology has long been a.

Men5CV: Hope for Ending Africa’s Meningitis Epidemics

Men5CV: Hope for Ending Africa’s Meningitis EpidemicsA landmark global health study led.

Stem Cell Therapy Shows 92% Success in Corneal Repair

Stem Cell Therapy Shows 92% Success in Corneal RepairA groundbreaking stem cell therapy known.

Gene Therapy for Maple Syrup Urine Disease

Gene Therapy for Maple Syrup Urine DiseaseResearchers at UMass Chan Medical School.

How Fast Are Your Organs Aging? Simple Blood Test May Tell

How Fast Are Your Organs Aging? Simple Blood Test May TellNew research from University College London.

HEALEY Platform Accelerates ALS Therapy Research

HEALEY Platform Accelerates ALS Therapy ResearchA New Era of ALS Clinical.

Low-Oxygen Therapy in a HypoxyStat Pill? Scientists Say It’s Possible

Low-Oxygen Therapy in a HypoxyStat Pill? Scientists Say It’s PossibleA New Approach to Oxygen Regulation-HypoxyStat.

Leave a Comment