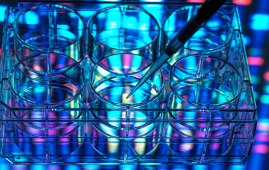

By strengthening the body’s own mucosal layer, researchers have created an inhalable powder that could shield the lungs and airways from viral invasions like flu and COVID. In mouse and non-human primate models, the powder, known as Spherical Hydrogel Inhalation for Enhanced Lung Defense, or SHIELD, decreased infection over the course of a 24-hour period. It can be used repeatedly without impairing normal lung function.

“The idea behind this work is simple—viruses have to penetrate the mucus in order to reach and infect the cells, so we’ve created an inhalable bioadhesive that combines with your own mucus to prevent viruses from getting to your lung cells,” says Ke Cheng, corresponding author of the paper describing the work. “Mucus is the body’s natural hydrogel barrier; we are just enhancing that barrier.”

Cheng is a professor at the NC State/UNC-Chapel Hill Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering and the Randall B. Terry, Jr. Distinguished Professor in Regenerative Medicine at North Carolina State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. The non-toxic ester is grafted onto gelatine and poly (acrylic acid) to create the inhalable powder microparticles. The microparticles swell and attach to the mucosal layer when exposed to a moist environment, such as the respiratory system and lungs, increasing the “stickiness” of the mucus.

The first eight hours after inhalation are when the effects are at their peak. Over the course of 48 hours, SHIELD biodegrades and is totally eliminated from the body. In a mouse model, four hours after inhalation, SHIELD stopped SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus particles with 75% effectiveness, which decreased to 18% after 24 hours. When testing for the H1N1 and pneumonia viruses, the researchers discovered comparable outcomes.

In a non-human primate model of both the original and delta SARS-CoV-2 variants, subjects treated with SHIELD had viral loads that were between 50 and 300 times lower than those of control subjects, and they showed no signs of lung fibrosis or inflammation that are typically present in primate infections. Viral load is the common measure used to assess exposure because monkeys do not display the same signs of infection that people do.

The researchers also examined potential toxicity both in vitro and in vivo, finding that mice given daily doses of SHIELD for two weeks maintained normal lung and respiratory function and that 95% of cell cultures exposed to a high concentration (10 mg ml-1) of SHIELD remained healthy. “SHIELD is easier and safer to use than other physical barriers or anti-virus chemicals,” Cheng says. “It works like an ‘invisible mask’ for people in situations where masking is difficult, for example during heavy exercise, while eating or drinking, or in close social interactions. People can also use SHIELD on top of physical masking to have better protection.

But the beauty of SHIELD is that it isn’t necessarily limited to protecting against COVID-19 or flu. We’re looking at whether it could also be used to protect against things like allergens or even air pollution—anything that could potentially harm the lungs.”

The study appears in Nature Materials.

more recommended stories

Parkinson’s Disease Care Advances with Weekly Injectable

Parkinson’s Disease Care Advances with Weekly InjectableA new weekly injectable formulation of.

New Blood Cancer Model Unveils Drug Resistance

New Blood Cancer Model Unveils Drug ResistanceNew Lab Model Reveals Gene Mutation.

Osteoarthritis Genetics Study Uncovers New Treatment Hope

Osteoarthritis Genetics Study Uncovers New Treatment HopeOsteoarthritis- the world’s leading cause of.

Antibody Breakthrough in Whooping Cough Vaccine

Antibody Breakthrough in Whooping Cough VaccineWhooping cough vaccine development is entering.

Scientists Unveil Next-Gen Eye-Tracking with Unmatched Precision

Scientists Unveil Next-Gen Eye-Tracking with Unmatched PrecisionEye-tracking technology has long been a.

Men5CV: Hope for Ending Africa’s Meningitis Epidemics

Men5CV: Hope for Ending Africa’s Meningitis EpidemicsA landmark global health study led.

Stem Cell Therapy Shows 92% Success in Corneal Repair

Stem Cell Therapy Shows 92% Success in Corneal RepairA groundbreaking stem cell therapy known.

Gene Therapy for Maple Syrup Urine Disease

Gene Therapy for Maple Syrup Urine DiseaseResearchers at UMass Chan Medical School.

How Fast Are Your Organs Aging? Simple Blood Test May Tell

How Fast Are Your Organs Aging? Simple Blood Test May TellNew research from University College London.

HEALEY Platform Accelerates ALS Therapy Research

HEALEY Platform Accelerates ALS Therapy ResearchA New Era of ALS Clinical.

Leave a Comment