According to Sarah Yip, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and the Yale Child Study Center, mapping out teenage brain development can help predict current and future dangerous drinking behavior.

During adolescence, adolescent brains are rapidly creating new connections. Two of the systems that are rewired at this time are reward and inhibitory networks, which develop differently in males and females.

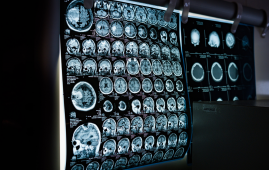

Yip and her colleagues examined a vast MRI dataset of teenage brain development to see whether they could predict drinking behavior in teenagers by looking at how these two systems reorganize during development in a study published in JAMA Psychiatry. The study discovered that the development of inhibitory and reward pathways, which widely influence “brake” and “go” behavior, can help predict how likely those youths are to drink substantially in the future.

The study found that how the brain responded during inhibitory and rewarding tasks could predict how likely kids were to engage in dangerous drinking in the future. However, whereas data from both tasks might predict alcohol consumption in girls, only data from the inhibitory test could predict behavior in guys. According to Yip, taking a deeper look at these systems could help researchers design new therapy for alcohol use.

Creating a map of the adolescent brain

Not only do bodies change during adolescence. Any parent will tell you that their children’s behavior changes dramatically during their adolescence. However, the shape of these modifications can differ between people and sexes.

Girls, for example, establish their inhibitory systems (the connections that tell them not to do something) earlier than boys. This could explain why researchers often notice differences in drinking habits between males and females during adolescence, with boys being more prone than girls to participate in dangerous drinking behavior.

Yip and her colleagues, including Sarah Lichenstein, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry; Godfrey Pearlson, MBBS, MA, professor of psychiatry and neuroscience; and Qinghao Liang, PhD candidate, wanted to explore if they could detect these gender variations in the brain. “We knew there could be sex differences in the development of alcohol use,” she explains. “So [we wanted to know] whether different brain networks might be related to alcohol use in men versus women.”

The researchers sought to look for gender differences using cutting-edge machine learning. To accomplish so, they needed a large amount of data to train their system. Yip and her colleagues therefore used MRI pictures from the IMAGEN collaboration, a European research that collected genetic and neurological data on about 2,000 teenagers.

14-year-olds were asked to do various tasks while their brains were examined in an MRI as part of this study. Some of these tests were designed to activate participants’ reward and inhibitory systems, such as having them play a game for money or avoid pressing a button in response to a stop signal. These same teenagers were then brought back when they reached the age of 19 to take the same examinations.

A once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to study teenage brain development across time

The researchers were able to map out how the brain developed over a five-year period by tracking these youngsters over time. This type of dataset is “very rare,” according to Yip. As a result, it is “uniquely poised to allow us to ask questions that we haven’t been able to ask before,” she says.

This includes issues such as whether brain development can predict drinking habits. Yip and her colleagues searched for patterns in brain connectivity in 1,359 of these kids to determine if they connected with how much they reported drinking as 14- and 19-year-olds.

Boys and girls were different

Their research found that links in at least two pathways could help predict the risk of binge drinking. However, whether the subjects were male or female determined which pathways predicted alcohol use. Only brain imaging data acquired during the inhibition task, which measures how well people “hit the brakes” on particular actions, could consistently predict drinking behavior in males. Female participants’ future alcohol usage was linked to brain imaging data gathered during both the inhibitory and incentive tasks.

According to Yip, one of the reasons could be that girls’ inhibitory circuits emerge earlier throughout puberty than boys’. To put these findings to the test, the researchers examined neural network patterns in 115 University of Connecticut students who were both older and geographically separated from the original European group. True to tradition, the same systems and gender disparities were observed in male and female students, implying that “even though it was different countries and settings, the same networks predicted risky drinking behavior,” according to Yip.

Researchers might theoretically utilize this information to design novel therapies for addressing dangerous drinking behavior in both youth and adults. These findings also imply that tailoring therapy to male and female patients may be a useful strategy for improving treatment outcomes. According to Yip, imaging these brain networks could help clinicians identify whether their treatments are effective for their patients.

more recommended stories

Dietary Melatonin Linked to Depression Risk: New Study

Dietary Melatonin Linked to Depression Risk: New StudyKey Summary Cross-sectional analysis of 8,320.

Chronic Pain Linked to CGIC Brain Circuit, Study Finds

Chronic Pain Linked to CGIC Brain Circuit, Study FindsKey Takeaways University of Colorado Boulder.

New Insights Into Immune-Driven Heart Failure Progression

New Insights Into Immune-Driven Heart Failure ProgressionKey Highlights (Quick Summary) Progressive Heart.

Microplastic Exposure and Parkinson’s Disease Risk

Microplastic Exposure and Parkinson’s Disease RiskKey Takeaways Microplastics and nanoplastics (MPs/NPs).

Sickle Cell Gene Therapy Access Expands Globally

Sickle Cell Gene Therapy Access Expands GloballyKey Summary Caring Cross and Boston.

Reducing Alcohol Consumption Could Lower Cancer Deaths

Reducing Alcohol Consumption Could Lower Cancer DeathsKey Takeaways (At a Glance) Long-term.

NeuroBridge AI Tool for Autism Communication Training

NeuroBridge AI Tool for Autism Communication TrainingKey Takeaways Tufts researchers developed NeuroBridge,.

Population Genomic Screening for Early Disease Risk

Population Genomic Screening for Early Disease RiskKey Takeaways at a Glance Population.

Type 2 Diabetes Risk Identified by Blood Metabolites

Type 2 Diabetes Risk Identified by Blood MetabolitesKey Takeaways (Quick Summary) Researchers identified.

Microglia Neuroinflammation in Binge Drinking

Microglia Neuroinflammation in Binge DrinkingKey Takeaways (Quick Summary for HCPs).

Leave a Comment