Scientists report that a novel approach to treating HIV that involves transplanting stem cells resistant to the virus from umbilical cord blood has produced long-lasting positive results. The “New York patient,” a middle-aged mixed-race lady with leukemia and HIV who has been HIV-free since 2017, was effectively treated with the method. The likelihood that HIV can be cured through stem cell transplantation in people of all racial origins increases when stem cells from cord blood are used instead of suitable adult donors, as has previously been the case. The researchers share the full results on March 16 in the journal Cell; preliminary details on the case study were presented in February 2022 at the 29th annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

“The HIV epidemic is racially diverse, and it’s exceedingly rare for persons of color or diverse race to find a sufficiently matched, unrelated adult donor,” says Yvonne Bryson of UCLA, who co-led the study with fellow pediatrician and infectious disease expert Deborah Persaud of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Using cord blood cells broadens the opportunities for people of diverse ancestry who are living with HIV and require a transplant for other diseases to attain cures.

Antiviral medications, while effective, must be used permanently in order to treat the over 38 million persons living with HIV worldwide. In 2009, the “Berlin patient” became the first person to be HIV-free, and two additional men—the “London patient” and “Düsseldorf patient”—followed suit in 2010.

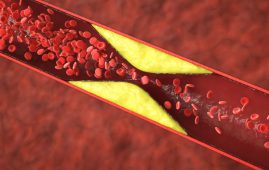

In all three cases, the donor stem cells came from adults who were compatible or “matched” and had two copies of the CCR5-delta32 mutation. This mutation confers resistance to HIV by preventing the virus from entering and infecting cells. All three of the patients underwent stem cell transplants as part of their cancer treatments.

The CCR5-delta32 mutation is extremely rare in other populations and affects just about 1% of white people. Since stem cell transplants often require a close match between donor and recipient, this rarity restricts the possibility of transplanting stem cells with the advantageous mutation into patients of color.

The team decided to try to treat the New York patient’s cancer and HIV at the same time since they knew it would be nearly hard to identify a matched adult donor with the mutation. Instead, they implanted CCR5-delta32/32-carrying stem cells from stored umbilical cord blood. Thanks to a group of transplant specialists led by Drs. Jingmei Hsu and Koen van Besien, the patient underwent her transplant in 2017 at Weill Cornell Medical.

Her case was a part of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Network and the NIH-sponsored International Maternal Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials (IMPAACT) Network (ACTG). To boost the likelihood that the surgery would be successful, stem cells from a patient’s relative were combined with umbilical cord blood cells. According to Bryson, cord blood may contain less cells and take a bit longer to populate the body after being administered. The cord blood cells are given a boost by combining stem cells from a patient’s matched relative with cord blood cells.

The patient’s leukaemia and HIV were effectively put into remission as a result of the transplant, and this remission has now persisted for more than four years.

The patient was able to stop using HIV antiviral drugs 37 months following the transplant. She has now remained HIV negative for more than 30 months since quitting antiviral therapy, according to the doctors who are still keeping an eye on her (at the time that the study was written, it had only been 18 months).

“Stem cell transplants with CCR5-delta32/32 cells offer a two-for-one cure for people living with HIV and blood cancers,” says Persaud. However, because of the invasiveness of the procedure, stem cell transplants (both with and without the mutation) are only considered for people who need a transplant for other reasons, and not for curing HIV in isolation; before a patient can undergo a stem cell transplant, they need to undergo chemotherapy or radiation therapy to destroy their existing immune system.

This study is pointing to the really important role of having CCR5-delta32/32 cells as part of stem cell transplants for HIV patients, because all of the successful cures so far have been with this mutated cell population, and studies that transplanted new stem cells without this mutation have failed to cure HIV,” says Persaud.

“If you’re going to perform a transplant as a cancer treatment for someone with HIV, your priority should be to look for cells that are CCR5-delta32/32 because then you can potentially achieve remission for both their cancer and HIV.”

The authors emphasize that more effort needs to go into screening stem cell donors and donations for the CCR5-delta32 mutation. “With our protocol, we identified 300 cord blood units with this mutation so that if someone with HIV needed a transplant tomorrow, they would be available,” says Bryson, “but something needs to be done [on] an ongoing basis to search for these mutations, and support will be needed from communities and governments.”

more recommended stories

Is Prediabetes Reversible through Exercise?

Is Prediabetes Reversible through Exercise?150 Minutes of Weekly Exercise May.

New Blood Cancer Model Unveils Drug Resistance

New Blood Cancer Model Unveils Drug ResistanceNew Lab Model Reveals Gene Mutation.

Healthy Habits Slash Diverticulitis Risk in Half: Clinical Insights

Healthy Habits Slash Diverticulitis Risk in Half: Clinical InsightsHealthy Habits Slash Diverticulitis Risk in.

Caffeine and SIDS: A New Prevention Theory

Caffeine and SIDS: A New Prevention TheoryFor the first time in decades,.

Microbial Metabolites Reveal Health Insights

Microbial Metabolites Reveal Health InsightsThe human body is not just.

Reelin and Cocaine Addiction: A Breakthrough Study

Reelin and Cocaine Addiction: A Breakthrough StudyA groundbreaking study from the University.

Preeclampsia and Stroke Risk: Long-Term Effects

Preeclampsia and Stroke Risk: Long-Term EffectsPreeclampsia (PE) – a hypertensive disorder.

Statins and Depression: No Added Benefit

Statins and Depression: No Added BenefitWhat Are Statins Used For? Statins.

Azithromycin Resistance Rises After Mass Treatment

Azithromycin Resistance Rises After Mass TreatmentMass drug administration (MDA) of azithromycin.

Generative AI in Health Campaigns: A Game-Changer

Generative AI in Health Campaigns: A Game-ChangerMass media campaigns have long been.

Leave a Comment