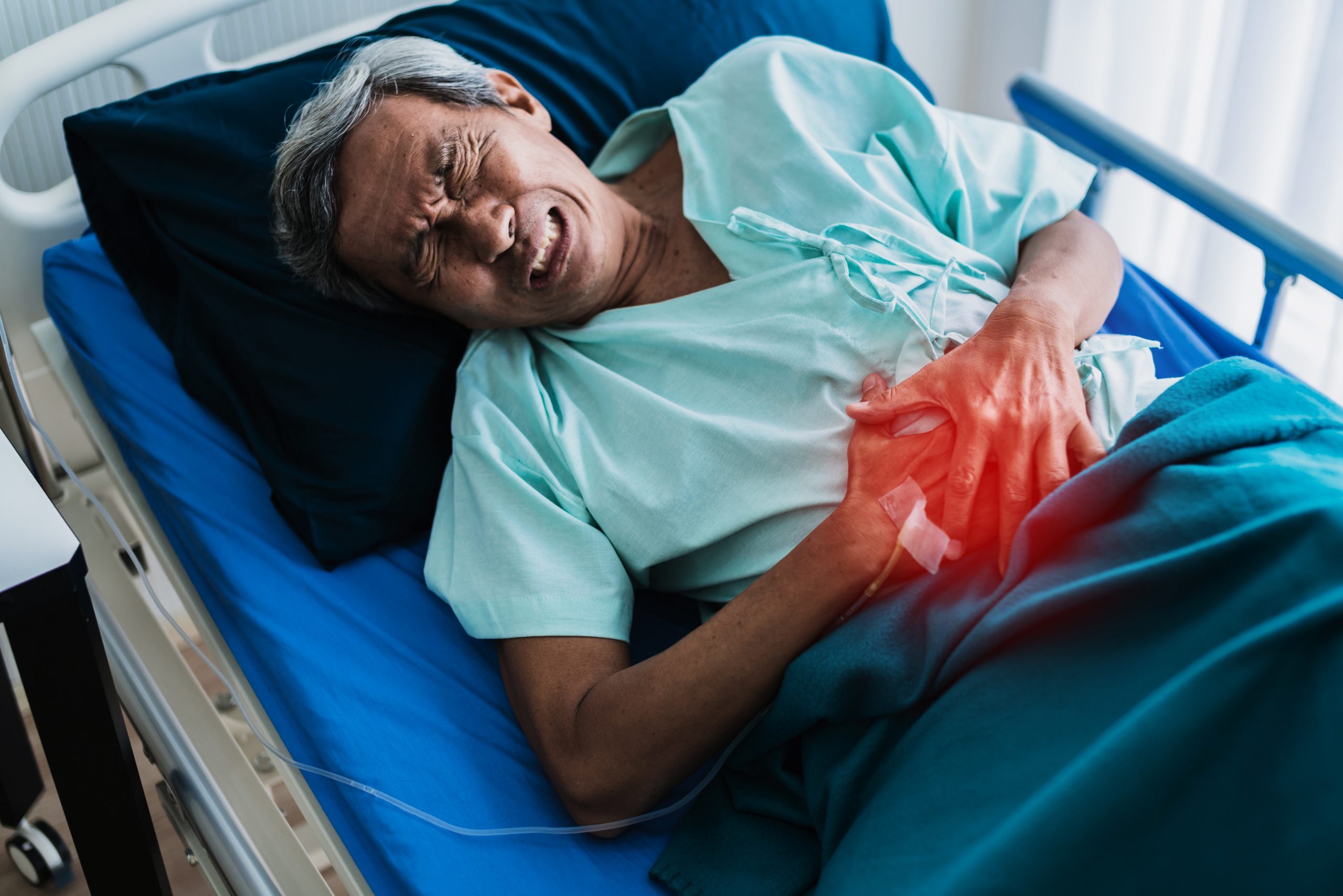

According to a study from researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine, tumors frequently release chemicals into the bloodstream that pathologically modify the liver, sending it into an inflammatory state, causing fat accumulation, and hindering its typical detoxification processes.

The possibility of novel diagnostics and medications for identifying and reversing this process is raised by this study, which sheds light on one of cancer’s more cunning survival strategies.

In the study, which was published in Nature, the researchers discovered that extracellular vesicles and particles (EVPs) containing fatty acids secreted by a wide range of tumor types that are developing outside the liver can remotely reprogram the liver to a condition approximating fatty liver disease. The livers of cancer patients and animal models of the disease both included signs of this mechanism, according to the researchers.

Our findings show that tumors can lead to significant systemic complications including liver disease, but also suggest that these complications can be addressed with future treatments,” said study co-senior author Dr. David Lyden, the Stavros S. Niarchos Professor in Pediatric Cardiology and a professor of pediatrics and of cell and developmental biology at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Lyden and his research team have been examining the systemic consequences of tumors for the past 20 years. Lyden is also a member of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center and the Gale and Ira Drukier Institute for Children’s Health at Weill Cornell Medicine. These outcomes highlight certain tactics that tumors employ to ensure their survival and hasten their development.

For instance, in research presented in 2015, the team found that extracellular vesicles containing chemicals secreted by pancreatic malignancies are taken up by the liver and prime the organ to encourage the establishment of new, metastatic tumors.

Using animal models of breast, bone, and skin cancers that metastasis to other organs but not the liver, the researchers found a new set of liver abnormalities brought on by distant cancer cells in the new study. The major conclusion of the study is that these tumors cause an accumulation of fat molecules in liver cells, reprogramming the liver to mimic the fatty liver disease, an obesity- and alcohol-related disorder.

The scientists also found that reprogrammed livers have low amounts of the cytochrome P450 enzymes that break down potentially harmful chemicals, such as numerous medication molecules, and high levels of inflammation, as indicated by raised levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF-). The observed decrease in cytochrome P450 levels might be the reason why chemotherapy and other medications are frequently intolerable to cancer patients as their condition worsens.

This liver reprogramming was linked by the researchers to EVPs, which are released by distant tumors and transport fatty acids, including palmitic acid. The fatty acid cargo causes the Kupffer cells, which are immunological cells found in the liver, to produce TNF-, which in turn promotes the development of fatty liver.

Although the study’s main focus was on animal cancer models, the researchers found that newly diagnosed pancreatic cancer patients who later had non-liver metastases had similar liver alterations.

“One of our more striking observations was that this EVP-induced fatty liver condition did not co-occur with liver metastases, suggesting that causing fatty liver and preparing the liver for metastasis are distinct strategies that cancers use to manipulate liver function,” said co-first author Gang Wang, a postdoctoral associate in the Lyden laboratory. Jianlong Li, a scientific collaborator in the Lyden laboratory, is also a co-first author of the study.

The scientists hypothesize that fatty liver disease aids cancer development in part by converting the liver into a lipid-based energy source.

“We see in liver cells not only an abnormal accumulation of fat but also a shift away from the normal processing of lipids, so that the lipids that are being produced are more advantageous to the cancer,” said co-senior author Dr. Robert Schwartz, associate professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Weill Cornell Medicine and a hepatologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

That could not be the only advantage that tumors gain from this liver change.

“There are also crucial molecules involved in immune cell function, but their production is altered in these fatty livers, hinting that this condition may also weakens anti-tumor immunity,” said co-senior author Haiying Zhang, assistant professor of cell and developmental biology in pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine.

By employing techniques like preventing tumor-EVP release, restricting the packing of palmitic acid into tumor EVPs, stifling TNF- activity, or removing Kupffer cells in the experimental animal models, the researchers were able to lessen these systemic effects of tumors on the livers.

The possibility of using these techniques on human patients to obstruct these distant effects of tumors on the liver is still being explored by the researchers. They are also looking into the possibility of using the finding of palmitic acid in tumor EVPs circulating in the blood as a potential early warning sign of advanced cancer.

more recommended stories

Atrial Fibrillation in Young Adults: Increased Heart Failure and Stroke Risk

Atrial Fibrillation in Young Adults: Increased Heart Failure and Stroke RiskIn a recent study published in.

Neurodegeneration Linked to Fibrin in Brain Injury

Neurodegeneration Linked to Fibrin in Brain InjuryThe health results for the approximately.

DELiVR: Advancing Brain Cell Mapping with AI and VR

DELiVR: Advancing Brain Cell Mapping with AI and VRDELiVR is a novel AI-based method.

Retinal Neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s Disease

Retinal Neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s DiseaseBy measuring the thickness of the.

Epilepsy Seizures: Role of Astrocytes in Neural Hyperactivity

Epilepsy Seizures: Role of Astrocytes in Neural HyperactivityRoughly 1% of people experience epilepsy.

Role of Engineered Peptides in Cancer Immunotherapy

Role of Engineered Peptides in Cancer ImmunotherapyIn a recent publication in Nature.

CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Therapy for Prostate Cancer

CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Therapy for Prostate CancerIn their preclinical model, the researchers.

Epilepsy Surgery: Rare Hemorrhagic Complications Study

Epilepsy Surgery: Rare Hemorrhagic Complications StudyFollowing cranial Epilepsy Surgery, hemorrhagic complications.

Pediatric Epilepsy – Mental Health Interventions Unveiled

Pediatric Epilepsy – Mental Health Interventions UnveiledMental health challenges frequently manifest in.

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Boosts Ovarian Cancer

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Boosts Ovarian CancerDuring the COVID-19 pandemic, US women.

Leave a Comment